The picture of the truth-seeking scientists sitting alone in their ivory towers is often used negatively. Instead, science is supposed to drive society forward, to create impact, provide solutions, and to be the basis of growth and prosperity. I argue that this expectation is detrimental for science and society. It creates a toxic scientific system with too many incentives to break the rules, and it hinders society to face its most important challenges. Seeking the truth and nothing but the truth is enough of a societal responsibility for science. At the end, some practical suggestions how to conquer back the ivory tower are given.

This post was also submitted to FQxI’s essay contest “How could science be different?” and was selected for an Honorary Mention Price.

It’s a Monday afternoon in April this year. Together with approximately twenty other senior postdocs I’m sitting in a nice and old palace-like building in the middle of a big European city. We are here for a mandatory training session of our funding agency to become junior research leaders. Today’s session is about “Persuasive Science Communication”. We form small groups sitting around tables and are asked to prepare a few sentences describing our research that we can “pitch” in front of some “stakeholders”. The task is then that one group member pitches their sentences in front of our trainers (two ex-BBC journalists) who play the role of some stakeholder. My group decides that it would be most interesting if I presented my research, as it seems the most difficult to explain to non-experts. Thus, imagining that the fictitious stakeholders were interested laypersons, we think about how we could describe emergence—the idea that “the whole is greater than the sum of its part” and that new effective laws at the macroscale can emerge from the laws that govern the microscale (think about the laws of thermodynamics arising from the interplay of many many atoms). One of the trainers is going around and asks us about our plans. She decides that my subject is too complicated and that we should prepare something more tangible, and in any case one of the other tables is already preparing something about fundamental science. We quickly settle on another person who has indeed a very sexy sentence to start with: “One out of four people will suffer from a brain disease during their lifetime…” For the role play involving the “fundamental science” table our trainer plays the CEO of Intel, and my fellow has to convince them to invest into developing super fast computers such that we can continue at the pace of Moore’s law.

On day 2 the morning session is devoted to “Driving Societal Impact through Research” and the afternoon session is about “Innovation: Connecting Research with the Market and Society at Large”. The topics are the creation of value, the generation of societal impact, how to build a research based company, and how to become an entrepreneur. Advancing the knowledge of mankind per se does not play any role on this day. I’m feeling tired and have difficulties staying awake…1

In an attempt to stay awake—and surrounded by words like pitching, stakeholders, impact, value, innovation, society, etc.—I start thinking about what science should be: how should we as a society view science? what is its purpose, value and mission? I quickly settle on the idea that science should be about truth—and nothing but the truth. To be clear, when saying “truth” I do not mean it in any absolute sense but as a systematic procedure to get closer to the truth using “scientific methods”, i.e., methods that we deem verifiable, rational, objective, etc.2

If we accept this view of science, then it follows—by use of the scientific method—that any “persuasion” in front of “stakeholders”, any aspired “societal impact” or any “connection of research with the market” is unscientific. This does not imply that any of the aforementioned things are automatically bad or evil. It simply means that a scientist trying to persuade stakeholders, trying to create a societal impact (other than the pure distribution of knowledge or truth) or trying to connect their research with the market is no longer speaking as a scientist. That person is then always speaking as a person with certain self-referential interests, may they be the acquisition of funding for research, the idea to get rich due to patents or spin-offs, the desire to get attention or become famous, among many other motives. While all these interests are understandable, they all create incentives to “bend the truth”: the scientist becomes a lobbyist, and this contradicts the view of science on which we assumed to agree.

Beyond doubt, it seems impossible to completely avoid such self-interested lobbying: when visiting colleagues I usually end up giving a seminar about my research. But it is equally beyond doubt that such self-interested lobbying can have very bad societal consequences [1]. Today, at a point where human society faces pivotal challenges, not being clear about the sole purpose of science as a systematic way of truth seeking causes in my view a vicious circle of the following three main problems.

First, as already indicated above, by pushing scientists into the role of lobbyists fighting for funding, money, attention or fame, one creates incentives to bend the rules in one’s own favour. The list of examples of rule bending is long, and it extends from big scandals (e.g., direct manipulation of scientific data or plagiarism) into a large gray zone (promising more than what is possible, ignoring counterevidence, favoritism, selective citations, referee reports reaching from useless to evil, etc.).

Second, it creates both false impressions for and false expectations of society, where science is too often associated to the idea that everything becomes “better” and that it can solve all problems that appear. A recent example being the global Covid-19 pandemic, in which the discernible public debate quickly narrowed down to one major topic: the vaccine. Turning to long term trends during the 20th century, I believe that science has even replaced in large parts the role of religion of promising a better life (at least in western societies). This seems a reasonable conjecture in view of the rapid and parallel growth in scientific knowledge, technological capabilities and wealth. However, science is, and always has been, also about limitations: just think about the laws of thermodynamics (all of them), that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light or the incompleteness and uncombutability à la Gödel and Turing [2]. From this point of view, it no longer appears surprising that denialism and conspiracy theories thrive once one hits a problem (think climate change) that can no longer be simply solved by some new technologies (besides scientists, think lobbyists, still claiming that it can). I believe that parts of this problem could have been avoided by emphasizing from the beginning on that science is “only” about seeking truth—independent of the question whether this truth is comfortable, useful or profitable.

Third, false impressions in society (among other factors, of course) create false political decisions that shape the (currently toxic) scientific system. Truth seeking is inherently an unpredictable and time-consuming endeavor that requires transparency, collaboration (plus a healthy dose of competition), trust, flat hierarchies and a diversity of scientific characters. These desiderata seem quite obvious and natural, but once one adds the rule that “scientists should create a better world” desiderata start to shift because the word “better” is most often not (solely) meant to be “closer to the truth”. Consequences are an unnecessary increased competition, incentives to optimize unscientific performance goals, increased bureaucracy to organize the competition and to monitor “scientific” success, disappearance of critical voices, appearance of scientific bubbles, a boring uniformity, among many others things. It is not my intention to allocate the fault to one of the three sides of either scientists, society or politics, nor to distribute it between them. I rather want to show how these three perspectives mirror and magnify each other, and that the common source of error is to view science as something else than systematic truth seeking. Once again, this does not imply that things outside science (e.g., trying to transform a scientific insight into a market-ready technology) are bad. These involve important steps, but they should not be labeled as science.

So how can we turn the tide and generate a win-win situation, where scientists no longer take the role of an “Eierlegende Wollmilchsau”3 and society at large, and also other stakeholders, get trustworthy science? Clearly, there are fundamental problems in our society that prevent us from finding a perfect solution, for instance, the fact that our political voting system favors short term interests whereas future generations have zero voices—certainly not optimal if we want to also find uncomfortable truths. However, I want to end this essay by discussing some practical solutions that should be in reach if only the scientific society wants them.

First, somewhat ironically, we scientists must become lobbyist for the sake of science, and convince stakeholders close to our circle of influence (e.g., scientific societies, networks, publishers and funding agencies) to correctly communicate what science is about (and what it is not about), that it is by itself an integral part of human culture, and one of the greatest endeavors of mankind. As an example, let us see what the EU legislation on research and innovation (EUR-Lex) has to say about it:

Research and innovation (R & I) contribute directly to our level of prosperity and the well-being of individuals and society in general. […] With a budget of €95.5 billion, […] the EU’s ninth multiannual framework programme for R & I is designed to facilitate and strengthen the impact of R & I in supporting and implementing EU policies, while tackling global challenges. It creates jobs, boosts economic growth, promotes industrial competitiveness and optimises investment impact within a strengthened European research area.

Research and innovation statement of the European Union (accessed April 29, 2023)

Okay, to be fair, the text does not even mention the word “science”. But the problem exists even at smaller scales, where one would expect a closer connection to science. For instance, many of the most wanted scientific journals are very explicit about their goal to publish high impact results and directly ask referees whether they are persuaded that the paper is a key or highly significant contribution. Neglecting one decisive aspect of the problem (namely, what does “impact” even mean?), I believe it is a fact that a referee can not objectively judge these questions (the history of science literature is flooded with examples). Again, this policy creates incentives to bend the rules. Referee reports containing purely subjective impressions (without further solid justification) such as “this paper is too technical, not broad enough, not well presented, not impactful enough, etc.” are the (apparently frequent) consequence, but it is even more unfortunate that editors seemingly rely on them without hesitation. I believe that we as a scientific community have the chance to change this situation, e.g., by explicitly pointing out that judging the precise degree of impact is unscientific (and not our task), and by creating alternative community journals such as SciPost or Quantum.

A second practical solution that I like to put forward concerns the allocation of research funding. As emphasized above, science requires a transparent and trustworthy system supporting a diversity of research characters, but at the same time scientific progress is also inherently risky and unpredictable (“there is no royal road to science” according to Karl Marx). These evident insights are not new, but as a cynic I would describe the current scientific system as a system where good proposal writers instead of good scientists thrive. So how can we change the situation without creating new false incentives or additional administrative burdens? I came to the conclusion that the only democratic way to distribute funding under uncertain conditions is to play the lottery and to distribute the funding more evenly. Specifically, suppose an agency wants to fund one hundred proposals with 1,000,000€ grants, but receives one thousand applications. How to choose the lucky 10%?4 I believe it is best if a committee of scientists (ideally randomly chosen from a variety of related but not too close disciplines), perhaps aided by computer algorithms, filters out proposals that do not meet some minimal acceptance criteria (which might be variable) and finally settles on, say, the best 300 proposals. Among those 30% the lottery decides who gets funded.5 This way of distributing funding is not only more democratic, unbiased and, at its heart, more scientific—it also has the immediate advantage that it reduces time-consuming report writing or discussions for those evaluating the proposal to a minimum. It also appears likely that proposal writing itself becomes easier, as the (unscientific) fine details what exactly you do in five years from now become irrelevant. I can only see a win-win situations for all sides here.

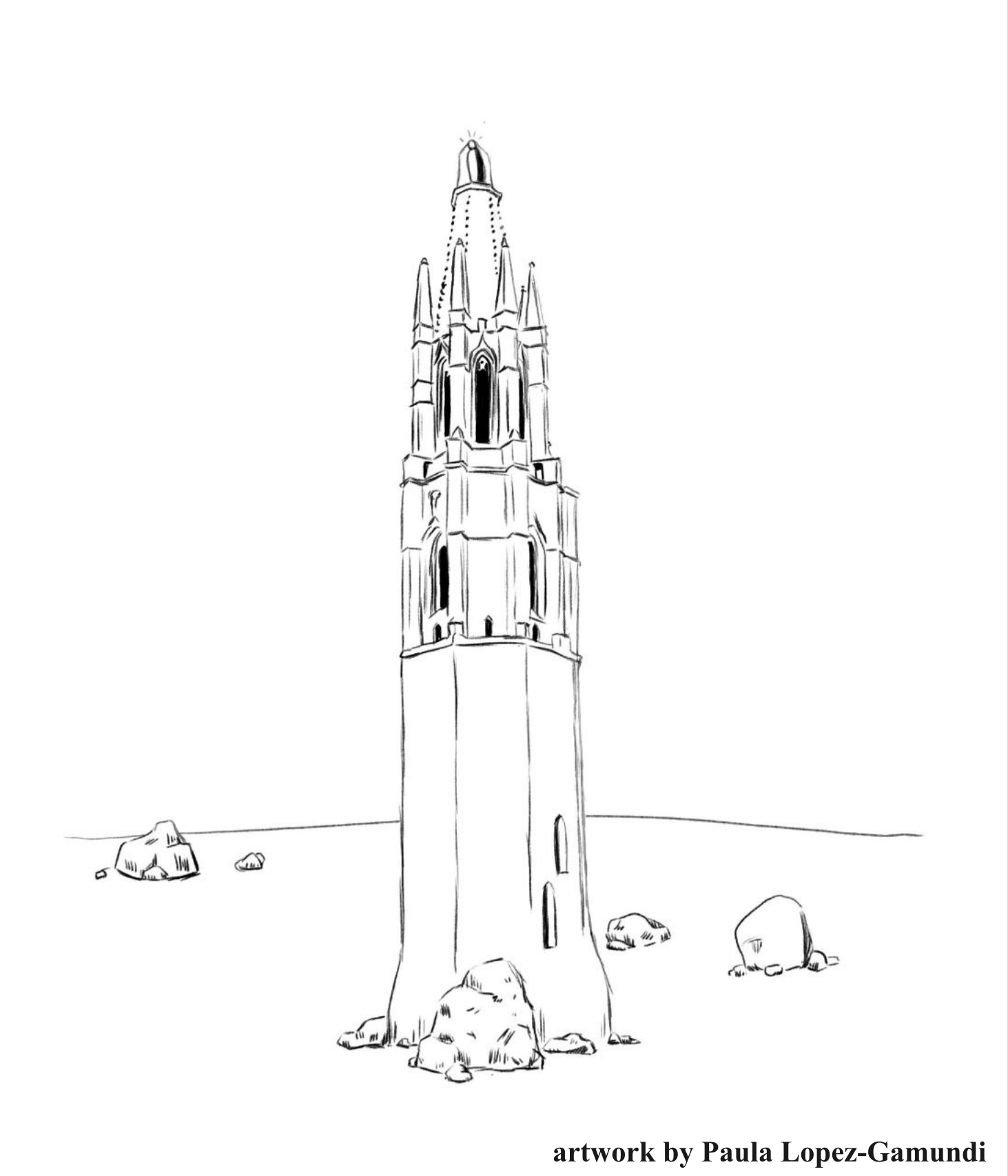

To conclude, standing up for the truth and nothing but the truth, even if you stand on an ivory tower, is an important societal responsibility in itself. In view of the problems that both science and society faces, I believe it is time to conquer back the ivory tower. There are many stairs to be climbed, but at least it seems unoccupied.

References

[1] N. Oreskes and E. M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2010).

[2] A. Aguirre, Z. Merali, and D. Sloan (editors), Undecidability, Uncomputability, and Unpredictability (Springer, Cham, 2021).

Footnotes

- The morning session of day 3 was about “Research Integrity”, which got a great response from the audience. Since the research background of my fellows is very mixed, I also enjoyed watching their responses and comments on day 1 and 2. Not to forget the food, drinks and social activities, of course. ↩︎

- This essay is about the relation between science and society, and not about the nature of the scientific method. To make my point in the following, I have to rely on the reader not to get distracted, e.g., by questioning the precise definition of the words rational or objective. ↩︎

- Literally translated from German this means “egg-laying wool-milk-pig”, and it refers to a marvelous pet being able to meet all demands at once. Here, it refers to a scientists that is supposed to be a scientist (in the strict sense above) plus a perfect educator, communicator, persuader, entrepreneur, grant proposal writer, administrator, group leader, role model, … ↩︎

- And why not funding 200 grants with 500,000€ instead? I am not aware of any scientific evidence showing that one giant research group with twenty people performs better than four groups with five people. ↩︎

- Various slight modifications of this procedure are conceivable, of course. For instance, if one proposal is so good that it instantly convinces the entire committee its chances for funding could be increased accordingly. ↩︎

Leave a Reply